Ed Charles from Tomato, followed through on a meme from Lucullian Delights to interview another blogger with five questions. Here are the questions Ed sent me with my responses.

1. How long have you lived in Cambodia and why did you move there?

Just over two years. Why? Lack of decent fermented fish in Australia, and the result of the 2001 Australian election made moving to a fish-filled, single party state seem much more appealing.

2. Could you explain how blogging has had a positive (or negative) effect on your life/work?

Work-wise, it’s a massive positive. I finished my full-time job just over a month ago and at the moment I’m food and travel writing professionally for my remaining few months in Phnom Penh. Without blogging, I’d now be unemployed. I’ve got an article and photo in today’s Wall Street Journal Asia on fish amok and a few more food and travel articles forthcoming. In my non-travel writing work (marketing with a copywriting/web bent), the blog makes for a handy portfolio.

Life-wise, blogging lets random strangers have a forensic account of what I eat upon which they can comment. I’m still unsure whether this is a good thing or not. I’ve also met a few other bloggers who happen to be in Cambodia and elsewhere, and they all seem to be not as freakish as you’d expect from people that you meet at random from the Internet. After I was in the local newspapers, a few restauranteurs have recognised me when I’ve been eating at their restaurants and accost me for not reviewing them.

3. What do you miss from Australia in terms of culture and food?

Lamb. The many cultures that eat lamb.

4. Where else (if anywhere) would you like to live in the world and why?

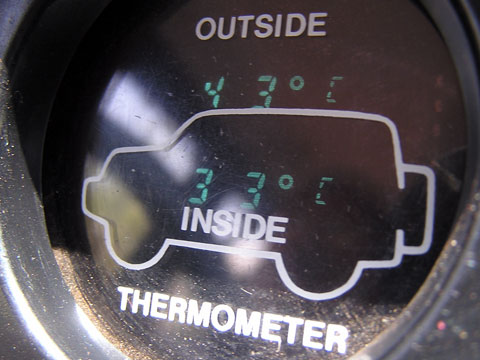

Thimpu, Bhutan. It’s so hot right now.

I’m open to moving anywhere that isn’t being shelled by somebody nor can be described as ‘post-genocide’. Living in Phnom Penh has made me realise that I can make the best out of living in most cities. The new E3 visas that Australians can get to work in the USA makes either the Bay Area or New York very tempting, but in all likelihood, I’ll be back in either Melbourne or Sydney for some time.

5. In your view what’s the biggest problem with Cambodia and is there any hope in it being solved?

This will be controversial regardless of which problem that I pick: the depth of (sometimes vested) interest in every problem in Cambodia amongst business and development professionals fuels intractable debates. There are many problems, each more problematic than the next.

With that broad disclaimer, my pick for biggest problem: complete lack of the independence of the judiciary and the rule of law. It is what underpins civil society and provides a base for all other development. The Hon Justice Michael Kirby AC CMG who took on the task early on in Cambodia’s rebuilding outlines the problem much more eloquently than I ever could:

On my initial visit to Phnom Penh I found that there were virtually no judges. No courtrooms. No officials. No laws. When we consider the challenge of international law and order, it is vital to remember that, in many countries, even the most rudimentary of governmental institutions may be missing. Any judge of the old regime in Cambodia who did not flee the country was almost certainly murdered by the Khmer Rouge. Accordingly, Cambodia had to start again. I remember vividly speaking to the new “judges” in what had been the old courthouse in Phnom Penh. None of them was a lawyer. Most of them were teachers. At least they could read and write. They asked me rudimentary questions about what it meant to be a judge.

Could they remain members of a political party? Could they accept presents? What would they do if there was no law on the subject? My task, with judges from India, Zimbabwe, France and elsewhere, was to offer a crash course in the judicial function. Similar courses have been given under the auspices of the United Nations before and since. Most recently, in East Timor, judges from many lands are working with locals to rebuild a rudimentary system for the administration of justice.

These are the truths of many countries. I explained to the “judges” in training that it was unacceptable for them to receive gifts. If a gift were accepted from a large multinational corporation, happy with the outcome of a case, it would soon become known. No one would trust the decision of that judge. Yet I was told that it was a strong tradition in Khmer culture to offer gifts of friendship and gratitude in certain situations. I warned that this was intolerable in judicial office. The eyes of my listeners were downcast. Later it was explained to me that judges in Cambodia received as salary $US20 a month. The only way they could survive would be by occasional gifts. Only in that way could they educate their children. I saw a look of anguish in the eyes of the new “judges”. I could perceive their dilemma. The notions of “privatisation” had combined with cultural politeness to suggest the supplementation of meagre public salaries. Police and guards on roadways in Cambodia regularly levied “tolls”. It was a kind of users’ contribution to the pockets of the lonely guards performing a sometimes dangerous job. Yet judges are supposed to be in a different class, I insisted. The eyes were lowered further. I was demanding a rule that it was almost impossible to live by.

There can be no global rule of law without an uncorrupted judiciary. Nations can enact laws. They can subscribe to solemn international declarations. They can ratify treaties. But unless those who enforce the law are uncorrupted, it will mean little or nothing. Reliance on the uncorrupted decision-maker is something we take for granted in developed countries. But in most countries of the world the judges and magistrates are underpaid, if they have been paid at all.

My endeavours to persuade the World Bank to interest itself in the underpinnings of governance in Cambodia, fell on deaf ears. This was before the new head of the Bank, Mr James Wolfenson, an Australian, took it, with other global institutions, down the path of strengthening governmental infrastructure. Without an infrastructure of integrity, talk of money laundering laws and extradition or of drug law enforcement and international police cooperation, is rather empty. In many countries of the world the absolute prerequisite to a just, efficient and lawful implementation of high standards against international economic crime is simply not present. This is why the new interest in governance of the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organisation, the OECD, the Commonwealth of Nations and other bodies is to be applauded. Without independent and impartial courts, the building of a global rule of law will enjoy only selective success.

I don’t believe that this problem is impenetrable – if I did I would be consigning many of my good friends to a life of pointless work and a hopeless fate.

Want me to interview you?

- Leave a comment saying, ‘Interview me.’ I’m on the road at the moment, so I might take a while to interrogate you.

- I will respond by emailing you five questions. Please ensure I have your email address.

- You will update your blog with the answers to the questions.

- You will include this explanation and offer to interview someone else in the same post.

- When others comment asking to be interviewed, you will ask them five questions.